Related Story: Means-testing for school fees of 457 visa holders

As Ireland's economy struggles to recover from the global financial crisis, more Irish than ever before are coming to Australia.

According to figures from the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 40,000 Irish people made Australia their home in 2011 and 2012 with 5,000 people settling here permanently.

Irish heritage minister Jimmy Deenihan says Australia's visa system makes it a popular target for young Irish professionals looking to establish their careers.

"There's a very friendly visa system that encourages young Irish qualified people and also skilled people to come to Australia," he said.

"People with PhDs, people who are highly skilled ... so it's a big gain for Australia but it's obviously a drain on the resources from Ireland.

"There’s huge connections here (in Australia) in the political world, in the education world, in the medical world and in industry.

"Irish people feel very comfortable coming to Australia because they know there’s a very positive welcome for them here.

Mr Deenihan says the Irish government is now looking to lure migrants back home."

"Now we are on a recovery trajectory, and hopefully some of these young people that are here in Australia, many on a temporary visa, will have the opportunity to return to Ireland, he said.

"That's the present government's ambition."

Around 50,000 holiday makers and backpackers from Ireland visit every year.

New wave of migration echoes colonial past

This new wave of Irish migration is an echo of Australia's colonial past.

Tens of thousands of Irish left the country for Australia in the decade after the great famine of the 1840s.

Author Tom Keneally says these migrants were ostracised.

"Towards the end of the great famine there was a build up of orphan girls so they were sent to Australia," he said.

"A hysteria developed ... they were the boatpeople of the 1840s and 50s, the lowest of the low, orphan kids who had seen terrible diseases ... and they had a huge impact on Australia because they now have hundreds of thousands of descendants.

"The famine cast a long shadow."

These migrants shaped Australia's political and cultural life.

By federation, up to a third of Australia's population were Irish migrants or their families.

"The Irish brought with them a profound sense of politics and they knew what social justice was," Mr Keneally said.

"They also brought a certain raucousness that people mistook for lowness of soul."

Economic woes driving Irish exodus

Ireland has in recent years returned to one of the top ten source countries for permanent migrants.

The Irish are now the seventh largest group choosing to settle in Australia, after India, China, the UK, the Philippines, South Africa and Vietnam.

This time around it is professionals who are leaving.

Four times the number of temporary skilled visas were granted to Irish citizens in 2012 compared to 2008.

Ireland's economic woes are driving this trend.

After a decade and a half of strong growth and investment that saw Ireland nicknamed "the Celtic tiger", the global financial crisis hit hard.

Ireland went into recession in 2008 and one year later the economy shrank by seven per cent.

Thousands of workers lost their jobs as the unemployment rate jumped from under five per cent to over 14 per cent.

Irish expats happy for work but struggle to build life in Australia

Construction worker Dot O'Gorman is one of those who came to Australia looking for work.

After a working holiday in Australia he returned home to Ireland in 2008.

Unable to find any work, two years later he decided to settle in Australia.

"In Ireland I could only get bits of work here and there," he said.

"Every day my girlfriend would go to work, and I would sit at home and watch TV with no work.

"You just get fed up. You're not getting anywhere in life."

He says if the economy does improve he will return home, but there is no sign of that yet.

Some Irish migrants struggle to build a life in Australia.

Counsellor Orlaith Sheill first came here for a backpacking holiday, and decided to stay.

She says some migrants feel grief and even anger at their homeland, for not being able to support them.

"Psychologically, the impact of migration is huge, the feeling that you don't have a choice versus gratitude that you can have a fresh start," she said.

"We cannot underestimate the guilt at saying goodbye, both for those who leave and for those who stay."

She says in a small country like Ireland, community ties are strong between families and neighbours.

"We're a very loyal people and to leave is disloyal and that is a hard burden to carry," she said

Photo: Bob Hawke, pictured campaigning earlier in the election, says the "absolutely terrible bias of the Murdoch press" is "unique" in his experience

Tony Abbott and the shadow minister for immigration, Scott Morrison, at a press conference in Darwin. Photograph: Mike Bowers/

Tony Abbott and the shadow minister for immigration, Scott Morrison, at a press conference in Darwin. Photograph: Mike Bowers/

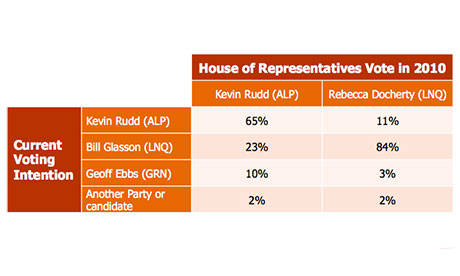

Swing in voting intention in the seat of Griffith Illustration: Lonergan

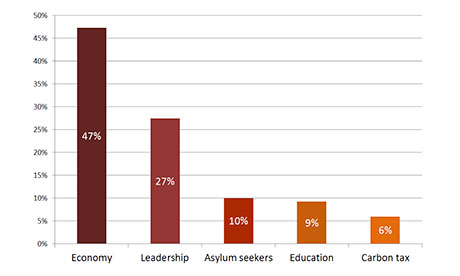

Swing in voting intention in the seat of Griffith Illustration: Lonergan  Responses to the question: "Which one of the following will have the most impact on how you will vote in this Federal Election? Illustration: Lonergan

Responses to the question: "Which one of the following will have the most impact on how you will vote in this Federal Election? Illustration: Lonergan